History

Home/History

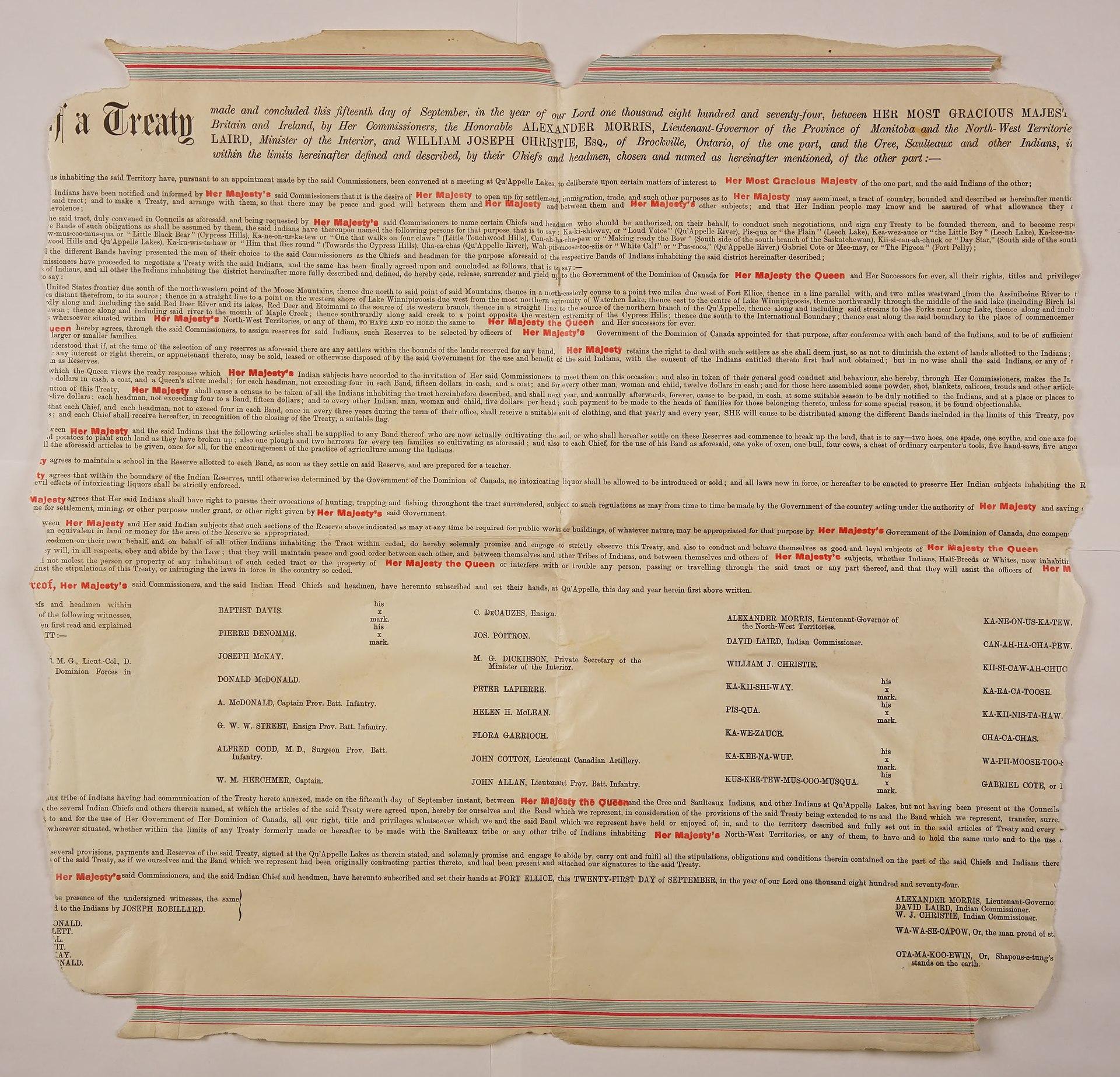

By 1870 the buffalo had disappeared and the and the Indian hunting grounds were being infiltrated by a growing number of white settlers. Tensions were mounting among the Indians who were nearing starvation and did not have the technical ability to start a new way of life. To solve these problems, it was decided by the Government of Canada to make treaties with the Indians giving them financial and technical assistance if they would agree to surrender all of their land except certain small reserved portions to the crown. Nearly all the Indian bands agreed to this plan. September 15, 1874 the Treaty #4 was signed in Fort Qu’Appelle, Gabriel Cote, who was head Chief of the Praire Saulteaux in Saskatchewan. In this treaty they gave up 74,600 square miles of land to the crown and agreed to live on reserves.

The band had the right to choose the site of their reserve, the site for the Cote Band was not selected until 1877, that’s why this is our Centennial year. It wasn’t until 1880 that the Pelly Agency was established before that the Band was administered by Birtle Mountain Agency. Chief Gabriel Cote’s headmen or councillors at that time were Wapiecake-cake(Whitehawk), Shingoish(Weasel)(Cote’s oldest son) and Charle Keesick. At that time the Cote Reserve was 56.5 square miles and the population was 250, and now the Cote Reserve is 31.7 square miles and the population is 1350. In 1904 famine struck the reserve and this was the same time the town of Kamsack and the railway was being built, in order to survive the Indians were forced to surrender 24.8 square miles of land for a mere$10.00 per acre, they received $2,030.00 which was used to purchase cattle and equipment for farming. At the time these lands were surrendered Joe Cote was the Chief. About a year after this surrender taken place a town place was being built, it is now named Kamsack. In takin this surrender, the Department made a farce of its earlier statements to the Band about the desirability of turning to grain farming over cattle raising, and at the same time demonstrated that it did not have the interest of the band at heart. After the 1904 surrender, the Department in an effort to discourage cattle raising began to sell off the cattle, and encouraged the young men to break land for growing wheat. However, just as this land was made ready for the first crop, the Department took this newly broken land as part of the 1907 surrender. Thus the Department took this newly broken land as part of the 1907 surrender. Thus the Department destroying the economic life of the Band. In getting rid of the cattle, it had removed the Band’s earlier economic activity: by taking away some of the best lands, these being the newly broken lands, which the Department had led the Band to believe were to become the new economic base for the reserve.

Although difficulties arose over disposal of all the land from the 1907 surrender ( not all the lands were sold at auctions, which is why they put more pressure on the civil servants to sell it privately) the Department by 1912 was willing to consider takin a new surrender of land from Cote Reserve.

However, by this time it was not the Department that took the initiative to open Indian land for settlement. The instigators of the idea of getting more land from Cote Reserve were the townspeople of Kamsack, and the settlers on the lands that had formerly belonged to the Reserve. These people were passing bribes and whiskey to the Chief and Councillors in the hope of convincing them to give up more land and were having a good deal of success in achieving their aim. Under the pressure and the inducement of bribes, the Band voted to surrender a two-mile strip of the Reserve.

At the signing of Treaty# 4, Lt. Governor Morris had promised the Indians that the Government would teach them “The cunning of the Whiteman” and the “help them put something in their land” He also said that these obligations would extend to future generations, for the “Queen thinks of children unborn, the Queen has to think of what will come long after today…’ The Cote Band was never taught “the cunning of the Whiteman”, in how to farm or develop its Reserve. Instead only bare rudiments of farming were passed on to the band, and this was done until 14 years after the signing of the Treaty.

In 1940’s a Community Farm had been tried, this had not been very successful and the land was turned over to individual Indian farmers or was leased to non-Indian farmers.

Under the terms of the #4, the government was obligated to build and maintain a school on the Reserve, this obligation was carried out first by a residential school at Crowstand, on the south side of the reserve and later by Day Schools.

The village of Badgerville was started in 1963 and it got it’s name from Hector Badger who was the Chief of the Cote First Nation at that time. The purpose of forming this village was to give the people better services and facilities at a lower cost. The present site of the old Agency.

Past Chiefs of Cote First Nation since 1874.

1874-Gabriel Cote

189?-Joe Cote

1912-jimmy Cote

1942-Donald Cote

1944-John Pelly

1946-Allen Fiddler

1956-Johnny Severight

1962-Hector Badger

1964-Johnny Severight

1966-Albert Cote

1969-Tony Cote

1974-Richard Whitehawk-3 months

1974-Tony Cote

1980-Norman Stevenson

1982-Alfred Stevenson

1984- Norman Stevenson

1986- Norman Stevenson

1988- Hector Badger

1992- Patrick Cote

1994 – George Tourangeau

1996- Lawrence Cote

1996- James Severight

2000-Norman Whitehawk

2016-George Cote

2019 – George Cote